Interview with a Raptor Researcher:

Patricia (Pat) Kennedy

February, 2024

At the last RRF conference in October of 2023, Pat gave our Friday morning plenary titled “A 50-year Perspective on Conservation of American Goshawks,” during which she offered a thorough account of her personal and our collective journey to better understand this revered species and other accipiters. At our 2022 meeting she was honored with RRF’s Hamerstrom Award, which recognizes those who contribute significantly to the understanding of raptor ecology and natural history. The following interview offers a deep dive into Pat’s trajectory as one of the first women to make a career out of raptor biology in the U.S. Her stories are illuminating, amusing, and rich with nuggets of insight for raptor researchers at any stage of career.

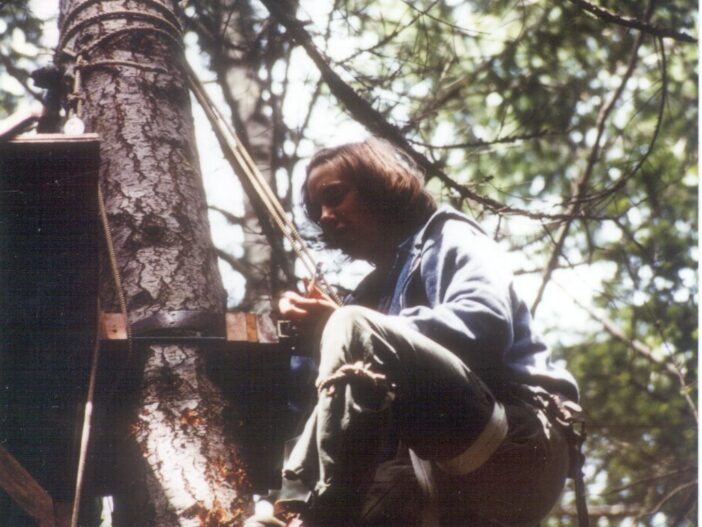

Pat with a Cooper’s hawk during her PhD in the mid-80's. Photo taken in New Mexico.

Patricia (Pat) Kennedy, Professor Emerita in Department of Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Sciences at Oregon State University

Years as an RRF Member: 53 years

Where she is from: South side of Chicago. I was a city kid and grew up in a multi-racial community near the University of Chicago.

Favorite Raptor: American goshawk (Accipiter atricapillus)

Second Favorite: Cooper’s Hawk, Accipiter cooperi

Current research projects: I am still working on the effects of land management on American goshawks and recently have become interested in writing biographies of other women who broke the glass ceiling in ecology and conservation biology.

When and how did you first become interested in studying raptors?

I got started as an undergraduate student. I went to a small liberal arts college called Colorado College and Dr. Jim (James) Enderson, an early member of RRF, was one of my advisors. He was trying to breed peregrine falcons in captivity, which hadn’t yet been done, and I was helping in his lab. At that point I was totally into raptors. I hadn’t picked a favorite, but the peregrine was a big conservation concern. Dr. Enderson took me to my first RRF meeting. He and Jerry Craig (Colorado Division of Wildlife) were instrumental in mentoring me and in getting the early peregrine captive breeding program going in the wild along with Cornell University. Tom Cade gets most of the credit, which he does deserve, but there were other people involved. After that first 1973 meeting, I was hooked and knew this was what I wanted to do. Until that point, I was going to be a veterinarian. Wildlife biology programs didn’t exist in urban areas so if you loved animals, it was not uncommon to be passionate about companion animals, especially as a woman. My dad didn’t hunt. He was realtor. I just saw wild animals in the zoo. I was a zookeeper at Brookfield Zoo in Chicago and worked at the Children’s Zoo at the end of my high school senior year, which exposed me to wild animals in a captive setting, and that was instrumental. I knew I could major in biology, because some women did, but still the only career track I saw was vet school. When I graduated high school in 1970 wildlife biologists were mostly managing game animals, and they were almost all white men. Urban wildlife programs came into existence when the field as a whole became interested in non-game animals, around the time of the Endangered Species Act. Before that wildlife management was all managing harvested and pest species. I entered college when this was all changing. The mid ‘70s offered a whole new job market for people to study non-game and endangered wildlife populations for Environmental Impact Statements.

Pat setting up a tree blind using spurs during her first field season in 1978. This blind was across from a Cooper's hawk nest.

What is it about the American goshawk that has kept you interested in them as a species over the course of your career?

I did my undergrad thesis on reverse size dimorphism (RSD), which is when females are larger than males. Accipiters were one of the groups with the most developed RSD and I was fascinated with them as a result. I ended up working on this topic for my thesis and then on Cooper’s hawks RSD for my masters degree which exposed me to other North American accipiters. I worked with the American goshawk for my PhD partially because there was funding, but also because it was becoming a hot conservation topic. After my masters I realized it was too hard to test many of the hypotheses about RSD. I had a great committee and they let me work on this, but they also kept me reigned in and asked how are you going to test this? What kind of data are you going to get? I thought okay, I’ll ask questions like do they eat different sized prey? This is what I worked on for my Cooper’s hawk masters. Then I realized it wasn’t a good topic because it's too hard to test. My committee convinced me of that, but I did a good enough job to get a degree and publish my findings in a scientific journal. Then I moved into forest management.

Cooper’s hawks are flexible birds. They weren’t a conservation concern, and the goshawk was. That’s how I made the switch. It took a lot of time to answer questions about the goshawk because they are so hard to find and there was a lot of litigation. I stayed in it because it was a fascinating bird to be working on. We needed to be working on other forest raptors besides the spotted owl, on other birds associated with old growth forest. There was a big issue with overharvesting of old growth. We were nuking the forests, and the spotted owl is almost extinct because of that. The next question was — is it the same with the goshawk? It wasn’t, but we needed to be looking.

Taken in 2003 in Japan, this photo shows Pat on a field trip to visit falconers flying golden eagles. This was after she gave a plenary on her goshawk research at an international raptor conference.

Can you share a career-changing moment?

Yes, when I decided to approach questions about goshawks using experiments rather than observational studies. This choice really affected how I did science. The biology we knew then pointed to the fact that prey abundance was really limiting goshawk reproduction and driving goshawk populations. To look at that, lots of people would have measured prey and followed reproduction at nests, but that’s a huge amount of work and I wanted to do it experimentally. I wanted to feed the goshawks at the nests in the wild. So, I did. I had two wonderful masters student and two goshawk populations, one in New Mexico and one in Utah, Joni Ward and Sarah Dewey. We fed them quail at the nest and looked at how it affected juveniles. Our research question was: how does food supplementation affect the success of juveniles?

Influencing extra food at the nest did not influence reproductive success but did influence juvenile survival. We thought if there is lots of food at the nest, the female doesn’t have to hunt, so supplementing food for the female means she can protect the nest from predators. We monitored juvenile survival and how often females left the nest, with radio transmitters, and found that on nests we fed, the female stayed put. I’m convinced that her ability to stay on the nest made a big difference in survival of the young. She is a good nest defender. For the nests that were fed, the juveniles stayed at the nest longer, but at unfed nests, fledglings left much earlier. The biggest mortality time for raptors is in their first year. Most juvenile goshawks die once they leave the nest, something between 80% and 90%.

This experiment worked great. It was a huge amount of work, and everyone told me I was crazy for doing a food supplementation experiment with goshawks. Inside I thought, maybe they’re right this is nuts. Because of animal care issues we wanted them to take dead quail, not live, so we would gut freshly killed quail and put them at these platforms near the nest. For the first couple days the birds just keked at us and then fly found the quail and no one touched them, so we picked them up at night. I’d lie awake thinking please start taking these quail. Suddenly, on day three, one of the females finally grabbed one and took it to the nest. I was shocked. Then they all started to do it. But for that first week I was thinking what if this doesn’t work? Eventually we got great data. So that was my best career-changing moment; it really cemented my science philosophy around doing experiments if you can. It’s the only way to really see a cause and effect. I went on to do experiments whenever I could.

Can you share a memorable moment in the field? Why has this stuck with you?

During my PhD we were radio tracking Cooper’s hawks to look at prey delivery rates and I was asking how does hunting affect reproductive strategies of these two birds? We had radios on females and males and were following them trying to quantify energetics. Fledglings were a few weeks old, but they weren’t on nests. We didn’t have satellite transmitters, we were using low frequency transmitters that you had to have line of site on, and without that line you couldn’t find them unless you were in the air. On the ground you’re doing a lot of leg work to locate these birds. Females were predictable for a few weeks after leaving nest but then suddenly about half of them disappeared. I thought maybe there were bad batteries on these the birds, which was unlikely, but possible. I got mad at the telemetry company. I kept thinking I can’t believe this is a transmitter problem what the heck is going on. Then suddenly one of my technicians picked up the signal of one of the females we had lost, one that had disappeared for a few weeks. We were on a shoestring budget so I had to come up with money to get up in the air. I didn’t have access to a helicopter so I went up in a fixed wing that was for hire at the local airport. From there, we had much better range than on the ground, and we found the lost females on new territories. We figured out that females on nests where the males were doing good jobs would abandon the male and let him finish raising the kids, to enhance her survival over winter and migration. This was the first time this was seen in a raptor; female abandonment of the males, mate desertion. This became a big chapter in my PhD even though it had nothing to do with my proposal, and it added an extra year. I had to collaborate with a statistician, Elizabeth Kelly, to get help with my modeling approach, and she had other commitments but was an expert in dynamic programming, so it was worth the extra time.

This was a big aha moment – when you get faced with something really different from what you think you are studying, and your instincts tell you you’re onto something, go with it. My committee, to their credit said, okay go for it. They could have said no you gotta finish, it’s going to take you six years to do your PhD. Which is what it took. For me this was a lesson in hey, this is hot, and I may be wrong, but I’m going to go for it. It encouraged me for the rest of my life to take risks scientifically.

What piece of advice would you offer to those early in their career of raptor research?

Exactly that — to take risks scientifically. if you’re starting to do research you need to go out with hypotheses that you’re going to test, but don’t get fixated on them. People go out and do field work and then suddenly they get hit with an amazing weather event, maybe the worst drought that’s ever been recorded, and it changes the whole dynamics of what the birds are doing. Instead of worrying about it, take advantage of that opportunity and maybe ask some climate change questions. You want the hypothesis to provide you with structure, but if you find an aha moment, or an opportunity with some weird condition that wasn’t part of your plan, try and look at it creatively instead of worrying. Make it work for you.

Pat looking for ferruginous, red-tailed, and Swainson's hawk nests in NE Oregon at GPS locations of old nest sites recorded in the late '70's. This photo was taken in June 2012.

Your first RRF conference was in 1973. What do you remember most about that experience, and how would you characterize the value of the conference today?

In 1973 I was a junior in college, a naïve undergrad with a passion for animals. I knew a little about wildlife biology and raptors and was reading scientific literature, but really, I knew basically nothing. I had some field experience, and I was learning how to ask scientific questions. Then I went to this meeting and watched people presenting scientific papers on all sorts of birds that I was madly in love with, and they were doing wonderful work in both basic biology and conservation. For that first meeting the focus was on peregrine falcon recovery and I was able to see the context of what Dr. Enderson was doing, what we were doing, and how it fit into the bigger picture of peregrine falcon recovery. I saw how big the world of raptor science was. I had no idea! All these really smart people, very articulate, giving fascinating talks…I was totally blown away. I came back from that meeting, and I said I am going to be a raptor researcher. At the age of 20. No more vet school.

The other thing was the networking. Karen Steenhoff was my age, and at that meeting she and I were two of maybe four women in attendance. It was all white males. Karen was just out of college and had gotten a job with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Frances Hamerstrom was there, and she was famous. The guys to their credit, at least a few of them, particularly senior men, gave me some mentoring. You stick out like a sore thumb when you’re one of a few women, and you’re 20, and so I talked to people when I could. I was pretty extroverted, and I’d go up to people and say that was a great talk and ask stupid questions and as a result I started to think I can do this. An inkling. For some reason I was not intimidated by the fact that Hamerstrom was the only senior woman at the meeting. I noticed it but I didn’t dwell on it. I became one of the first females in a tenure track position in Wildlife Biology; I helped break the glass ceiling in academia. You get there by ignoring the obvious. You can’t focus on the fact that you’re the one and only in a room. It becomes too intimidating and stifling. This doesn’t mean bad things didn’t happen, and that people weren’t weird, but I dealt with them and then moved on and focused on talking to people who encouraged me.

As I continue to go to these meetings, I still see them as a great source of networking to talk about ideas and grant writing. You present your new ideas and get feedback. I think young people don’t realize how important professional meetings were, and still are. In my era we were just getting on computers. I did my masters thesis on a typewriter. Yes there is social media and online networking, and those are important, but I don’t think they are the same thing as a face-to-face idea swap. They are different types of interactions. Going to have a beer with someone after they give a talk is different from chatting online. But in context, when I was doing it, there weren’t alternatives for networking except for the phone. These meetings have been pivotal my whole career.

Pat in South Africa, looking through a spotting scope on a field trip at RRF's 2018 conference. Pat says this picture reminds her of another benefit to attending the annual conference - RRF has the best field trips!

There you have it — nuggets of wisdom from someone who followed her passion all the way to a glass ceiling and beyond. Pat has kindly agreed to be available for follow-up questions from our readers. I would especially encourage this for any early career raptor researchers (those we lovingly call ECRRs) who would like chat with a bonified raptor rockstar.

pat.kennedy@oregonstate.edu

Vida Libre: How a landfill is supporting Andean Condors in central Chile

February, 2024

Andean Condors scavenging at the landfill. All images courtesy of Eduardo Pavez.

One day in 2005, Eduardo Pavez was contacted by KDM Company, a landfill management operation in Central Chile. At the time of this call, he was researching condors and working as a wildlife consultant for Bioamérica Consultores. He had also founded one of the first rehabilitation centers for raptors in South America, which currently operates under the auspices of the Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile. Since 1993, the center has admitted 148 Andean Condors (Vultur gryphus) from what Eduardo refers to as “vida libre,” meaning free life. Of those admitted, 90 have been released back to their free life. Chile is a small enough country that Eduardo’s work made him the condor guy. KDM called because seven condors had been poisoned at their site, and they knew Eduardo could help.

Andean Condors are among the largest birds in the world. As obligate scavengers they rely on decaying animal matter, termed carrion, for sustenance. In central Chile, human livestock practices strongly influence the distribution of carrion available to Andean Condors. Landfills are predictable, and predictable food sources often alter the movement patterns of wildlife because understandably, most animals avoid working hard to find food if they don’t have to. Condors are no different.

On the day of that call, the seven poisoned condors were transported to the National Zoo’s veterinary clinic for care. Five of them died. The two that survived were transferred to Eduardo’s Raptor Rehabilitation Center where they recovered fully. Prior to release, one condor was fitted with a satellite transmitter. For three years Eduardo and his team were able to study that individual, and eventually they discovered the bird on a nest. A new vida libre.

Adult female soaring in central Chile with broad wings, some of the largest of any bird.

Although the presence of landfills can aid in condor survival by offering reliable food, they can also harm condors at the individual and population levels. Since the moment Eduardo was contacted by KDM, they have joined forces to study the relationship between condors and the landfill, in hopes of implementing measures to avoid negative impacts to the birds. One result of this collaboration has been a 17-year-long study of the site, during which Eduardo and his team have observed four poisoning events affecting 14 condors, 8 of which died as a result. Most of the afflicted were males, likely because adult males dominate over other condors at desirable food items. When those choice items are toxic, the males experience the worst of it. The poisonings were due to organophosphorus intoxication, which occurs when condors consume organophosphorus pesticides and suffer negative affects to the nervous system, and sometimes respiratory paralysis. The exact source of this poisoning was never revealed.

Additional findings from the study show that condor numbers at the landfill are directly linked to the presence of available food in the surrounding landscape, namely the carcasses of cattle and rabbit. Condor numbers at the site fluctuate depending on the movements of grazing livestock across the region. Notably, condor numbers at the landfill decreased between 2013 and 2016, correlating with widespread cattle mortality due to drought, and rabbit mortality due to myxomatosis disease. And influx of carcasses available on the landscape drew condors away from the landfill. After 2019 both mortality events subsided, and condor numbers at the landfill increased. Eduardo says that this trend “shows how the presence of condors in landfills offers an indicator, a very sensitive barometer, of what is happening with the food supply on a broad geographic scale.” Andean Condors star as proxies for the environmental health of the places in which they reside, a trait that many scavengers exhibit, but few receive credit for.

Another interesting finding over the course of the study was that the age and sex ratios of condors at the landfill suggest those at the bottom of the social ladder (juveniles and females) visit the landfill more often than adult males. Successful scavenging is more difficult for young birds and subordinate individuals. Landfills offer easier pickings for those who might be bullied off of choice carcasses by adult males elsewhere. Condors, like many large raptors, undergo a lot of trial and error in their first years of life as they learn how to obtain food successfully. For condors specifically, social hierarchies at feeding sites require skillful interpersonal navigation, and young birds usually get the short end of the bone.

A young male appears submissive in front of an old male. Condors are very hierarchical, with males dominating over females and the old over the young.

The results of this study were published in the December 2023 issue of the Journal of Raptor Research, in a paper titled “Landfill Use by Andean Condors in Central Chile.” The story has since been picked up by over eight news outlets around the world, including Spektrum, Science Magazine, LabManager, BNN, and Phys.Org. The popularity of this story speaks to the public’s interest in Andean Condors, as well as the uniqueness of this collaboration between a landfill management company and a passionate team of condor researchers. All too often we hear tales of companies abdicating responsibility for their role in affecting wildlife, but here, we see something different — shared intent to help these incredible birds stay healthy, to help them fulfill una vida libre.

Andean Condors, like all vultures, are important agents in the recycling of organic material across the landscape. They remove rotting flesh from the ground, for free, and they do it efficiently. Their continued existence in our skies is a worthwhile priority, not only in central Chile, but across the globe. After years of working with the condors, Eduardo speaks of them in poetic, strong terms — “When you contemplate the flight of the condor, it's easy to understand why it has been so relevant to Andean cultures since time immemorial. It is difficult to conceive a more beautiful, impressive, and harmonious spectacle. For many, he is the messenger, the one who carries men’s prayers to the top, where the Sun god lives. Working for the conservation of the condor is working for the conservation of an umbrella species, since under the shadow of its great wings inhabit many human and natural communities that need to be known and conserved.”

Adult male, probably of advanced age, due to the large size of the crest, dewlap, and folds on the head.

Meet Eduardo Pavez

Eduardo is general manager at Bioamérica Consultores and former president at the Unión de Ornitólogos de Chile. He is founder of the Rehabilitation Center for Birds of Prey of Chile and is the current director of the Andean Condor Conservation Project, or Manku Project, as it is known.

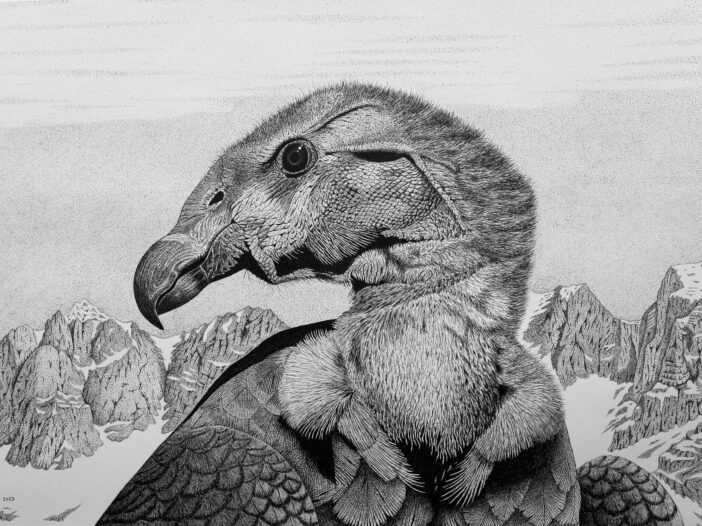

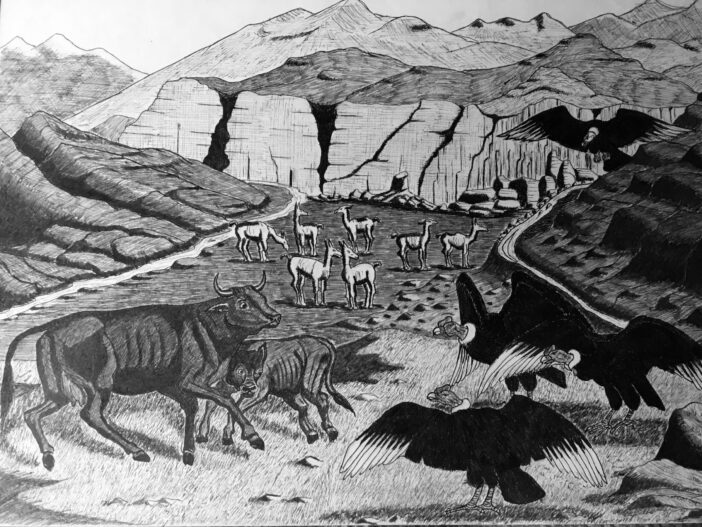

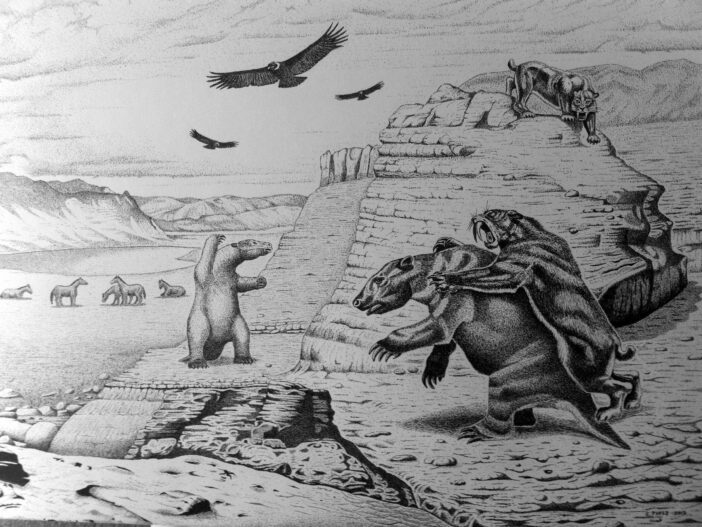

Andean Condor Art Gallery

Eduardo has generously offered to share here a collection of his scientific illustrations, done with rapidograph pens. Each drawing takes months of work. Among the intense daily activity, for Eduardo the hours of silence and thought, generally at night, is an activity that he considers therapeutic. Thank you Eduardo — for loving Andean Condors, and for depicting their beauty in memorable detail. These pieces speak for themselves. Welcome to the gallery.

Artist’s Statement

Eduardo, born and raised in Chile, has always been passionate about nature. In the early 80s, as a teenager, he self-taught himself to practice falconry with eagles and rehabilitate birds of prey. In addition to his work with captive raptors, Eduardo has dedicated much of his life to studying and observing them in nature. In addition to conducting research, he produces detailed illustrations of condors in a style reminiscent of the ancient naturalists whom he admires greatly. Eduardo has generously agreed to showcase some of his beautiful work here. In describing his hopes for this art, he says “sometimes a drawing, which is a representation of reality that passes through the filter of the artist’s consciousness, can transmit an even greater force than a photograph. Through my drawings I try to express what I feel and the strength that birds and condors transmit to me. I also intend to teach about their behavior, anatomy, or, in the case of condors, their physical characteristics associated with sex and age.” Eduardo also believes that portraying the condors in their natural habitat, and doing so in black and white, adds additional power to the impact of the illustration.

Juvenile female Andean condor less than one year old, recently hatched from the nest, faces the glaciers and cliffs of the Andes Mountain range of central Chile.

Adult female Andean condor, over eight years old, in the mountain range of central Chile.

Juvenile 3-year-old male Andean condor in the Cordillera del Paine, Chilean Patagonia.

Behind the clouds and the head of an adult male Andean condor hides the summit of Mount Aconcagua, the highest peak in the Americas with its almost 7,000 meters of altitude.

When I was 12 years old, I had to rest for several weeks due to an illness. To kill time, I made this drawing with a fountain pen, which turned out to be premonitory. At that moment, although I had been dreaming about birds for a long time, I did not imagine that in the future I would dedicate a large part of my life to condors.

Represents Patagonia during the Pleistocene. That was a time that I love, a time when animals populated the human spirit inspiring cave paintings, a time when the silhouettes of many species of giant vultures soared through the skies of the Americas.

I thank Zoey Greenberg and the prestigious Raptor Research Foundation for giving me the opportunity to disseminate part of our work and my modest naturalistic art.

Interview with a Raptor Researcher

At this year’s RRF conference in Albuquerque, Cheryl Dykstra received the Exceptional Service Award. This award recognizes RRF members who contribute outstanding work and service to the foundation. This year’s award goes to Cheryl for her notable work as Editor-in-chief of the Journal of Raptor Research (JRR), which just this year reached an all-time-high impact factor of 1.7. What follows is an interview with Cheryl on her career as a raptor researcher and editor.

Cheryl with a golden eagle, Aquila chrysaetos

Cheryl Dykstra, Editor-in-chief of the Journal of Raptor Research

Editor from: 2006 to current

Years as an RRF Member: 28 years (1995 – current)

Favorite raptor: Red-shouldered hawk

Current position: Owner of a small research and consulting firm, Raptor Environmental, and Editor of JRR

Current research projects: Breeding ecology of urban red-shouldered hawks; survival and movements of juvenile American kestrels; survival and movements of Henslow’s sparrows

When and how did you first become interested in studying raptors?

I love working with all bird species. I learned how to do ecological field and lab research doing my master’s degree on house wrens at the Leopold Reserve while at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. I then had the opportunity to pursue a Ph.D. studying Great Lakes bald eagles. In addition to working with such an iconic species, I knew it had to be easier to take blood samples from an eagle than from a wren! My research showed that the depressed reproductive rate of Lake Superior eagles was likely not a result of the legacy contaminants DDE and PCBs (which were decreasing), but was due to the natural low productivity of the oligotrophic Lake Superior. Since then, I’ve never looked back – I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to work with raptors ever since. I’ve studied urban/suburban red-shouldered hawks in southern Ohio for the past 25 years, and have also had opportunities to research barred owls and kestrels in this region.

How did you become involved with editorial work?

I’ve always enjoyed scientific writing, and the satisfaction that comes with finishing a project by sharing the results in a publication. My father worked as an editor for most of his career, and my brother started a journal and served as its first editor, so who knows? maybe it’s in my genes too.

My work with JRR started when former JRR Editor Jim Bednarz asked me to serve as an Associate Editor and then a couple years later asked if I was interested in being Editor when he retired from the position. So Jim is entirely to blame!

Since 2006, I’ve been the Editor for 71 issues (8057 pages) of JRR, and I’ve also enjoyed working with Clint Boal to co-edit a book, Urban Raptors: Ecology and Conservation of Birds of Prey in Cities.

What is your favorite part of being an editor for JRR?

I love helping first-time authors, students, and international authors get their research published in JRR. Sometimes they have a lot of questions and sometimes their manuscripts take a bit more work, but it is gratifying to help shepherd their papers into print.

I also love working with the editorial team. JRR’s Associate Editors, editorial assistant, translators, publications committee, and the rest of the team are amazing! They are top-quality researchers volunteering their time to put together our journal, and we couldn’t continue to improve JRR without their dedication and expertise. On top of that, they are just excellent folks to know and work with.

Can you share a memorable moment in the field? Why was it worth remembering?

During my Ph.D research in northern Wisconsin, I had to climb a white pine to retrieve a weather station and data logger that we had placed 85 feet up in a super-canopy tree. When we arrived at the tree one day in late summer, we found that wasps had built a nest about 60 feet high and 10 feet from the trunk, and were circling busily around it. I had been taught to climb trees using only climbing spikes and my hands, with no lanyard around the trunk and with my rope trailing behind (in retrospect, perhaps not the safest technique!). Without pausing to think, I climbed to the first branch, about 50 feet off the ground, emptied a can of Raid spray toward the wasp nest, and then quickly rappelled down. Later that day, I returned wearing long sleeves, gloves, and a mosquito headnet (did I mention it was near 90 degrees that day?). I resolved to “sneak” past the wasps, so I climbed the tree again and got my face stung three times through the headnet in the process. But I kept going and did manage to safely retrieve our weather station and data. I think the reason it was memorable was the combination of stupidity with success.

What is something you wish more people knew about raptors?

Because I’ve worked with urban raptors on private lands for more than 25 years, I get to interact with many landowners and answer a lot of their questions. My top three most common answers are:

1) No, my touching the nestlings will not cause the parents to abandon their nest.

2) No, that raptor won’t kill your dog or cat.

3) If raptors target your bird feeder, you’re still feeding birds, just different birds than you intended.

What has kept you invested in raptor work?

I think my answer will be the same as a lot of other folks in RRF. I’m passionate about raptors and want to contribute to their conservation, in whatever way I can. As we all know, raptor populations are vulnerable to anthropogenic threats and are likely to become more so in the face of increasing urbanization and climate change. Much of my research has focused on responses of red-shouldered hawks to urbanization, and I’ve been excited to see articles about their behavior, dispersal and survival, and reproduction published in JRR. And as a Christian, I also feel I can serve by doing my part to be a steward of the environment and the created avian biodiversity.

I’m also excited about talking to students about birds and conservation, helping them become engaged with the natural world. Raptors are fabulous “gateway” birds—few people can resist a raptor in the hand. Mentoring students and volunteer researchers in raptor and songbird research has been one of the highlights of my career.

And of course, working with raptors is just fun! I love being outside in wild areas, climbing to nests, and having an excuse to capture and study raptors. For my red-shouldered hawk research, I often get to travel to Hocking Hills in southeast Ohio, and I’ve enjoyed visiting raptor researchers studying Harris’ hawks in south Texas, peregrine falcons in Washington, and golden eagles in California. I also loved attending RRF conferences in places like Veracruz, Scotland, and South Africa.

What piece of advice would you offer to those early in their career of raptor research?

Keep at it—don’t be discouraged. Raptors (and other birds) need you more than ever. And don’t be afraid to contact us “senior” raptor professionals for help: advice, field opportunities, writing assistance, etc. We are a friendly lot (most of us!) and we sincerely want to help students advance their goals and careers. Volunteering with field research, at raptor rehab centers, or at your local museum or nature center is a great way to get started. Early in my career, I took classes at a field station, taught courses on ornithology, and volunteered with other graduate students to learn more about fieldwork. These are tough times for young wildlife ecologists, but all of us want you to succeed at bringing raptor conservation to the next generations.

You can view Cheryl and Clint’s book Urban Raptors: Ecology and Conservation of Birds of Prey in Cities here and explore the Journal of Raptor Research here.

Thank you Cheryl for all that you do!

It Began With a Vulture

Introducing your science writer and what it means

to be part of a raptor-loving community

Photo courtesy Mia McPherson

The Turkey Vulture was my spark raptor. In my early years as an intern-of-all-trades, I was at Penn State’s Shaver’s Creek Environmental Center training an adult male Turkey Vulture. He was, objectively speaking, a menace. He relished untying my shoelaces, tugging me off ladders, and dumping buckets of cleaning supplies when my back was turned. He pecked holes in my pants. Vomited on my shoes. But at the end of the day, he was the spunkiest bird in the place, and he learned fast. I grew increasingly fond of those hunched shoulders and featherless head, and endeavored to understand as much as I could about vultures in hopes of improving their reputation, at least locally. What a long road. Most visitors were so repulsed by him they fled the scene outright, seeking reprieve in the hawks next-door. Sometimes, people screamed. While this annoyed me, it also exposed me to a truism: everyone loved the other raptors. From the vulture enclosure, I had a secret mew-view of visitors as they strolled through the center, and their reactions were priceless — a child grabbing their parent’s hand to drag them in front of the Barred Owls, pointing and jumping, look how big their eyes are. A woman placing her hand on her chest, standing in front of the Golden Eagle speechless, her other hand on her partner’s arm. A teenager sitting on a rock, drawing the female Red-tailed Hawk, a perfect interpretation of predator unfolding on the page. Raptors evoke a slew of emotions that hook and reel people into new awareness. Seeing an owl up close can, it seems, facilitate a mental shift as significant as reconsidering the state of our planet and the way we treat the organisms we share it with. Visitors left the raptor center caring about the fate of those birds. Even when vultures were not included on their list of species to write home about, I was moved by the weight of the transformation. My interest in this human response, and my unsullied love for vultures, led me to a group of people who turned their own raptor response into a career — the Raptor Research Foundation (RRF).

I moved to Hawk Mountain Sanctuary to further my training in vulture conservation, and while there, became a member of RRF. In attending RRF’s annual conference I discovered a passionate, dedicated, and creative group of individuals who share a common goal of supporting healthy populations of raptors worldwide, vultures included. My first RRF conference was memorable — I strolled into a lobby and found folks with beers in hand, donning retro raptor t-shirts, and casually discussing Turkey Vulture genome sequences. Clearly, I’d found my crowd. I was at the conference to present a middle school curriculum I’d built on Black Vulture movement ecology, and as an educator, I was an outlier in a sea of numerically inclined researchers. They welcomed me nonetheless. I’ve attended the conference nearly every year since, and shared many more beers with researchers who are wing-deep in the complexities of raptor biology, and who recognize the value of education and art in furthering the holistic mission of raptor conservation. The challenge of supporting raptor populations is, of course, global in scope and therefore necessitates collaboration. RRF provides the community support, logistical framework, and intentional atmosphere for this collaboration.

Six years and a master’s degree later, I now have retro raptor shirts of my own, and I’ve joined the RRF team. I am your science writer. In this role, I will support the Foundation’s mission by disseminating information about raptors from the Journal of Raptor Research and other outlets within the society. It’s no secret that bridging the gap between academic research and the collective consciousness of the public is a big feat. We know that (most) raptors lend themselves to storytelling through their objective beauty, predatory prowess, and compelling life histories. They turn heads. Most fourth graders can list off several raptor facts, such as the speed of a Peregrine Falcon in a stoop, or the rotational capacity of an owl’s head. But the journey of how those facts reach their packaged and recitable form is often cloaked from the public eye. My job is to pull back that cloak — to craft writing that presents the academic accomplishments of the raptor research community to a broader audience, without compromising accuracy.

This post initiates a new RRF Blog which will serve as a platform for accomplishing these goals. On the blog you will find posts highlighting articles published quarterly in the Journal of Raptor Research, interviews with raptor researchers, guest blogs by members of the RRF community, notable member achievements, and more. At its core, this will be a hub for raptor research stories from multiple angles. For now, new posts will be announced on RRF’s Facebook and the announcement section of the RRF website. If you would like to post a guest blog on your focal species, the story of your project, or wish to nominate an interviewee for a raptor researcher highlight, please contact me at science.writer@raptorresearchfoundation.org. I can’t wait to hear from you.

Zoey is the science writer for the Raptor Research Foundation and the associated Journal of Raptor Research. She has spent over a decade writing and teaching about raptors. She is particularly interested in the lives of vultures and is a North American co-compiler for the IUCN’s biannual update on vulture research. She facilitates outdoor writing workshops for Freeflow Institute and works as a naturalist for Lindblad Expeditions. Zoey has a B.A in human ecology from College of the Atlantic and an M.S. in environmental studies from the University of Montana, where she wrote a thesis of prose poems critiquing conservation ethics. Zoey grew up in Bellingham, Washington, where the Salish Sea and temperate rainforest was a catalyst in sparking her love of the pacific northwest coast. When she’s not on ships or writing about raptors, she enjoys volleyball, ultimate frisbee, bellydance, and the color turquoise.