Conservation

CONSERVATION LETTERS

The Conservation Committee focuses primarily on writing and publishing Conservation Letters in the Journal of Raptor Research. Conservation Letters provide scientific reviews of matters affecting raptor populations globally. These letters are intended to be accessible to scientists, non-scientists, and policy makers, creating a go-to source for summaries of issues important to raptor conservation. Conservation Letters are intended to provide enough evidence-based examples that readers can appreciate the scope and prevalence of the issue described, and begin to understand lessons learned and potential solutions.

The Conservation Committee is Chaired by Dr. James Dwyer (jdwyer@edmlink.com), and is composed of the set of authors working on Conservation Letters at any given time. Committee membership rotates as letters are initiated, developed, and completed. As much as possible, each Conservation Letter is authored by a team composed of a lead author, a subject matter expert, and an early career raptor researcher (undergraduate student, graduate student, or recently graduated student). The Committee Chair serves as an author if necessary, but prefers to focus on assembling author teams and as the manuscript’s Associate Editor.

If you have an idea for a Conservation Letter, or are interested in helping as an author, please contact the Conservation Committee Chair. Early Career Raptor Researchers, Authors from outside of North America, and other groups under-represented in the field are especially welcome!

To date, the following Conservation Letters are published or are in press:

Conservation Letter: The use of drones in raptor research (In Press)

Authors: Spaulding, R., D.G. García, and D.M. Bird. 2024.

UAS view of a Prairie Falcon (Falco mexicanus) attending nestlings in a cavity nest in Canada. Photo credit: D. Zazelenchuk.

UAS view of an adult White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla) incubating a nest in Finland. Photo credit: T. Osala.

For more UAS images of nesting raptors, download the PDF of this Conservation Letter. None of the raptors in these images departed their nests during the inspections. RRF recommends that all drone operations follow local, state/province, and federal regulations regarding drone use.

Conservation Letter: Effects of Global Climate Change on Raptors

Authors: Marisela Martínez-Ruiz, Cheryl R. Dykstra, Travis L. Booms, Michael T. Henderson

A Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) nest blown from a cottonwood tree in a storm. Nest loss is part of life for raptors, but long-term intensive droughts related to climate change may be limiting growth of trees, thereby limiting new nesting opportunities. Photo credit: James Dwyer.

A Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) in a rainstorm. Evolutionary history prepares raptors for many storms, but the increases in storm frequency and intensity with climate change, including dangerous winds and hail, may exceed raptors’ ability to weather them safely. Photo credit: Jordan West.

Conservation Letter: Raptor collisions in Built Environments

Authors: Heather E. Bullock; Connor T. Panter; Tricia A. Miller

Barred Owl (Strix varia) impact smear on a window in Kansas, USA. Photo credit: Johnson County Community College Bird Collision Study

Short-eared Owl (Asio flammeus) killed in collision with either a vehicle or a glass highway sound barrier in South Korea. Photo credit: K. Young-Jun.

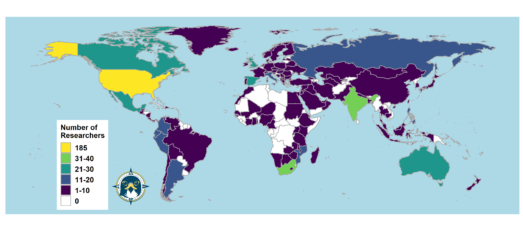

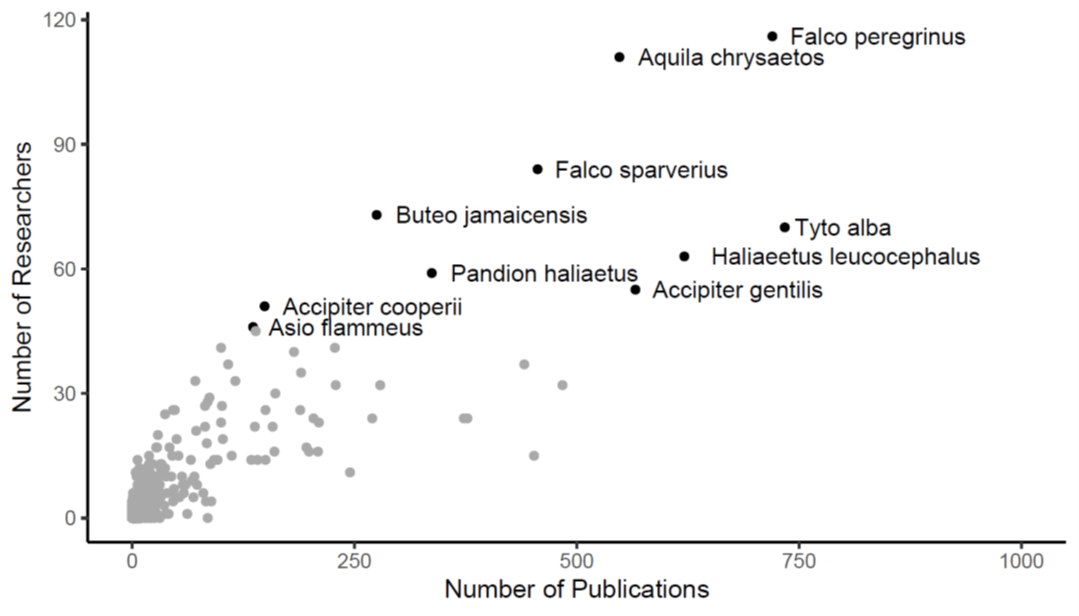

Conservation Letter: Monitoring raptor populations – A call for increased global collaboration and survey standardization

Authors: McClure, C.J.W., F.H. Vargas, A. Amar, C.B. Concepcion, C. MacColl, and P. Sumasgutner

World map indicating countries where respondents of a survey of raptor researchers are collecting data.

Number of survey respondents collecting data regarding a given species and the number of publications reported by Buechley et al. (2019) for that species. The black and labeled points in scatterplot depict the 10 most-reported raptor species by researchers and the grey unlabeled points depict all other raptor species.

Conservation Letter: Raptors and Anticoagulant Rodenticides

Authors: Eres A. Gomez, Sofi Hindmarch, Jennifer A. Smith

Stock photo of a wild, free-living rodent poisoned by an Anticoagulant Rodenticide (AR). ARs are pest control poisons designed to cause death by internal hemorrhage and bleeding, however death is delayed several days making slow-moving ill rodents easy prey targets for raptors.

Raptors such as this Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus) may be at risk of anticoagulant rodenticide exposure if they eat rodents which have consumed poisoned baits.

Conservation Letter: The Philippine Eagle as a case study in developing local management partnerships with indigenous peoples

Authors: J Kahlil Panopio, Marivic Pajaro, Juan Manuel Grande, Marilyn Dela Torre, Mark Raquino, Paul Watts

Forester Marilyn Dela Torre leading a community-based Forest Guard survey. Surveys such as these provide crucial information in understanding and managing effects of deforestation.

Deforestation is a threat to forest raptors, causing range reductions, isolations of subpopulations, reduced gene flow, extirpation, and local extinctions.

Conservation Letter: Lead Poisoning of Raptors

Authors: Julia C. Garvin, Vincent A. Slabe, Sandra F. Cuadros Díaz

Lead poisoning affects obligate and facultative scavengers globally. Lead is ingested when scavenging birds, such as the Crested Caracaras (Caracara plancus) pictured here, consume carcasses or gut piles contaminated with fragments of lead ammunition.

California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus) in flight. Lead poisoning is the primary cause of death of this critically endangered species.

Conservation Letter: Raptors and Overhead Electrical Systems

Authors: Steven J. Slater, James F. Dwyer, Megan Murgatroyd

A Great-horned Owl (Bubo virginianus) electrocuted on a distribution pole supporting energized equipment. Complex poles supporting equipment are associated with higher rates of electrocution than simpler poles without equipment.

A Common Buzzard (Buteo buteo) electrocuted on a grounded distribution pylon. Structures such as these, with grounded structural components near energized wires are associated with high rates of avian electrocutions, including but not limited to raptors.

Conservation Letter: Raptor Persecution

Authors: Kristin K. Madden, Genevieve C. Rozhon, James F. Dwyer

Raptor persecution is an ongoing pervasive, global conservation concern, with potentially significant impacts for some raptor species and populations. One common mechanism of persecution is poisoning, which caused the death of this White-tailed Eagle (Haliaeetus albicilla).

Persecution takes many forms, for example, this Ridgway’s Hawk (Buteo ridgwayi) shot and its feet collected.